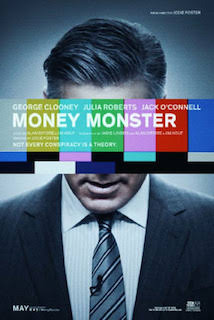

Jodie Foster Talks About Her New Film 'Money Monster'

Category: Movies

“They’re stealing everything from us, and nobody’s asking how,” anguishes Kyle Budwell, the gun touting protagonist of director Jodie Foster’s adrenaline fueled thriller Money Monster. As topical as today’s headlines – who hasn’t experienced that unmistakable pang of nervousness when the index precariously plunges? – Money Monster underscores just how little the general public knows and understands the true workings of the banking and financing industries.

The film opens on the cable television set of charismatic Lee Gates (George Clooney), a financial adviser, who doles out daily stock tips. Since Lee often goes off script, much to the chagrin of his producer Patty Fenn (Julia Roberts), the appearance of a delivery guy lurking off stage doesn’t set off any alarms, until he invades the stage and forces Lee to put on a vest laced with explosives.

The intruder is Kyle (Jack O’Connell), a working class guy from Queens, NY. Acting on a stock tip recommended by Lee, he invested in Ibis Clear Capital and lost his entire inheritance in what Lee dismissively labeled a “glitch.” Now, Kyle demands answers as to how Ibis managed to lose a cumulative $800 million. While Kyle’s rage and despair are palatable, Foster intersperses enough moments of spontaneous humor to ease the relentless tension and white-knuckle suspense. Adeptly acted and edited, Money Monster is both provocative and disconcerting.

What attracted Foster to the project? “For me it was primarily about the characters – two men, who changed each other, and the woman who was producing and directing their survival. It’s this American thing where you do the right thing. Take care of your mom, show up for work, you invest safely and there’s something waiting for you at the end of the day. In this case there isn’t and it sparks rage. That’s where Jack O’Connell came in and gave an extremely extraordinary performance,” explained the two-time Academy Award actress for 1988’s The Accused and 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs.

Making her directorial debut with 1991’s Little Man Tate, Money Monster is by far the most expensive and biggest effort to date. The 52-year-old actress didn’t stray from her established approach. “It’s kind of the same thing. You still have to ask yourself the same question – Is it true? If you start out with questions like will the audience like it? You make terrible mistakes, because you’re just deciding things out of fear. You want to stay close to the original idea,” she insisted.

Having committed nearly four years of her life to this project, Foster had to feel an emotional attachment to Money Monster. She agreed during a round of interviews in New York City, “Most importantly, does it move me? I still love it. When I tell a friend I get passionate and choked up about it. I don’t know if I’d make a movie where it’s just a bunch of pretty faces.

“The only way you can make choices is by knowing the characters and sort of have a personal investment in the film. That’s how you learn through the course of the movie. By the end you realize the personal connections.”

Even before yelling “action” for the very first scene, Foster had already made a heavy commitment in terms of time and talent. She outlined the process, “Along with the writers, we obviously did a lot of research in this incredibly difficult archaic world of finance, which few people understand.

“We knew what we wanted to say and it was rather a question of going in there and finding examples. I’m not sure there is a bad guy. Everyone has a point of view. Even in our film, Lee is saying, ‘Nobody was complaining when I was making them money. Everybody was looking the other way and wanted more stock, but the second I lost something everyone was concerned.’ It’s really quite true of what is happening in the financial world. Wall Street is going well and there’s no crash. Everyone wants to experience the bubble and doesn’t want to believe it’s going to end.”

Making her acting debut on television’s Mayberry RFD, however, it was in 1976 that Foster’s name became a household word, thanks to her controversial casting as teen prostitute Iris in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. The classic vigilante masterpiece starred Robert DeNiro as a lonely, honorably discharged US Marine, who takes a job as a cab driver to cope with his chronic insomnia. One of his fares is Iris, who is trying to duck her pimp (Harvey Keitel). DeNiro’s character Travis meets Iris for breakfast and attempts to persuade her to return to her family in Pittsburgh, eventually succeeding.

Just a few weeks ago, Taxi Driver celebrated its 40th anniversary with a screening at Manhattan’s Beacon Theater. Foster had seen it earlier in the week with a special guest – her 18-year-old son Charlie. She recalled, “It was the first time he’d seen it. I wanted to wait until he was old enough, not just because of the violence, but I think you have to be an adult to appreciate it.”

So what was Foster’s reaction? “So many things occurred to me as I watched the movie. It’s amazing how many racist names get called in that movie. I had forgotten and never even think about it at times. It was a different culture back then, certainly the world has become more violent. We were coming out of the 60’s and into the 70’s and out of Vietnam. There was a kind of meaningless among the returning vets feeling, ‘What can I do to feel like a man?” she said.

Given an honorary doctorate of fine arts from Yale University, the slim, blonde haired Foster labels her acting background as “the best film school I could have been given.” She said, “That’s especially true of someone like me who operates from her head. I’m so organized and obsessive. It’s such an amazing outlet and a way to learn the craft of filmmaking from the inside out.”

She continued, “The one thing I wished I’d learn before that first directorship assignment is not to control the actors, telling them exactly what to do. I really learned as the years went on that the best way to prepare them is to talk to them where their head is. To inspire them to create a well-designed machine of knowing exactly what we are trying to say.

“In the split second I say, ‘action,’ they are given a spontaneity and ability to try things, and not think about it too much,” she concluded.

About the Author

Winnie Bonelli is a former entertainment editor for a daily metropolitan New York City area newspaper. She is passionate about movies and television and loves to take readers behind the scenes.